There’s been considerable discussion in recent years about the value of more familiar, affordable 2D paving control platforms versus the seemingly more luxurious 3D solutions, with hardware costs often being the deciding factor. However, as with most technology investments, hard costs do not always tell a complete story.

When it comes to making the choice between 2D and 3D paving control systems, lifecycle benefits can certainly come into play in the way of improved productivity and efficiency. There is also a growing interest from public sector agencies assessing the value of these systems to achieve better quality surfaces, and thus lower maintenance and repair costs, which will likely dictate future specifications. Also, owners are starting to ask for as-built data gathered from machines, essentially a digital twin of current conditions, as part of the final delivery package to support future operations and maintenance.

Although there is increasing interest in digital solutions for asphalt paving projects, 2D versus 3D is not a one-size-fits-all decision in the paving world. To make an informed decision about 2D versus 3D, the following compares the two methods and provides a guide to help contractors assess where each is best deployed to achieve the optimal results.

Purpose-Driven Solutions

The fundamental difference between 2D and 3D paving is all in the means and methods. Put simply, 2D is referencing existing surfaces while 3D references a design.

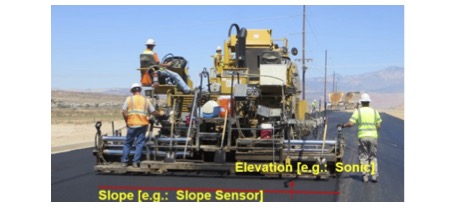

2D solutions reference existing surfaces and build up from that surface. From a technology standpoint, sonic or other sensors are used to calculate an average elevation for smooth paving, while a slope sensor determines the appropriate cross slope of the road (see Figure 1). A combination of stringlines and lasers could also be used – but there is no positioning system such as GNSS. As noted above, the system references the existing surface to assure that a consistent thickness of material is applied. Bumps and dips are not accounted for in the process but can be minimised using an averaging beam, and crews are typically placing a constant thickness over a base.

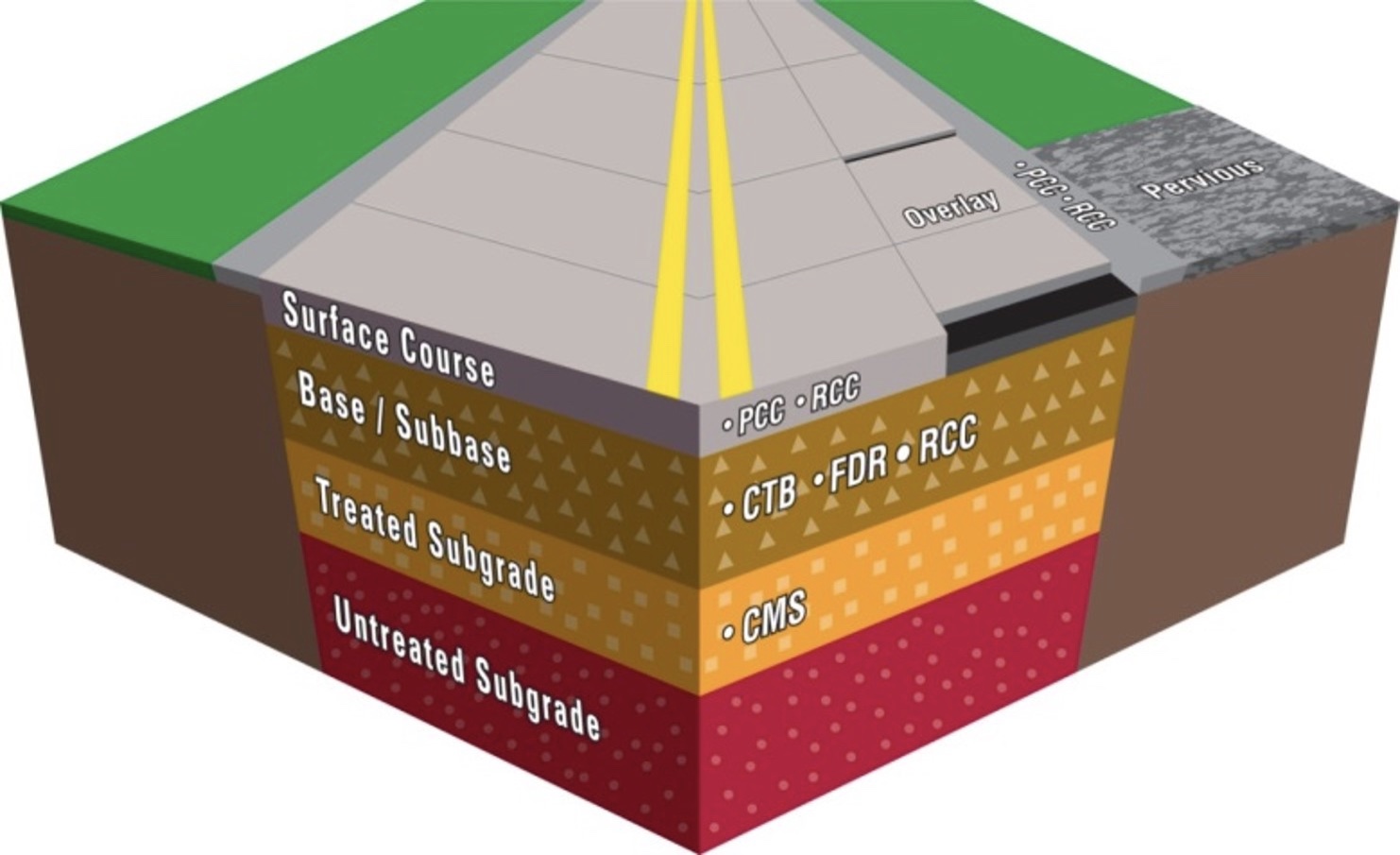

In comparison, 3D solutions reference a design – in essence an imaginary final surface plane – and builds down to the existing surface. A 3D paving solution relies on geopositioning, such as GNSS or a local site set up with total stations. With this solution, there is a z (elevation data) to go with the x,y grid, which is used to guide the machine to grade and slope according to the model. Using a 3D paving solution, the operator has a 3D elevation for each piece of the road bed construction (Figure 2).

While future 3D paving systems will likely include steering, in today’s environment, the positioning data delineates 2D paving from 3D.

Contractors might also have heard about a higher specification 2D, which we call 2.5D. This is a relative accuracy positioning system that is easier to deploy and works well when precision may not be as important as other factors. In this application, the user creates a cut/fill map, and instead of total station or GNSS to provide 3D positioning, the cut/fill map is overlayed on top of an existing surface scan and then onboard 2D sensors – such as sonic, slope or wire rope – that guide the machine. GNSS is likely only used to position the machine horizontally on the cut/fill map, not for absolute accuracy on the project.

A 2.5D solution is more expensive than 2D because of the GNSS component – for example RTK or VRS positioning – but it also reduces the need for fan lasers, total stations or other vertical augmentation devices.

The Best Fit

The option to use 2D, 3D or something in between is outcome dependent. Often, a 2D solution is good enough. For example, the 2D solution is an excellent option for roads that have already been milled or graded with a 3D system. However, if a project specification requires a finish at a verified elevation, you need 3D – even if the surface below was prepped with 3D.

Historically, 3D was only for high performance roadways, such as racetracks and airport runways. This isn’t the case anymore, however, as 3D systems have become more affordable and easier to deploy, and therefore are far more widely adopted today than they were even five years ago.

Many experienced contractors can improve final surfaces without 3D through the use of leveling systems or averaging beams, but that’s extra time on the job and more travel for the paver. The value of these solutions likely comes down to a measure of distance. If there are only subtle changes over short distances, an averaging beam does a great job. But for more complex scenarios or longer distances, those methods are likely too time and cost prohibitive.

Another point to consider is that some states are beginning to incentivise contractors to improve International Roughness Index (IRI) percentages. Instead of writing a specification that defines over and under limits with penalties for exceeding those limits, these specifications outline levels of improvement. The specification could state, for example, that the road condition starts with a defined IRI, and if the contractor can improve that IRI by 25%, 40% or 60%, they will be rewarded accordingly. In this scenario, the better the IRI, the more money the contractor makes.

Putting 3D Workflows to Work In Germany

Increasing demand for greater precision led milling and paving contractor KUTTER GmbH & Co. KG Construction Company, headquartered in Memmingen, Germany, to use its 3D paving workflows outside of typical practices. Previously only used on large machines with a milling width of at least two meters, the contractor put it to work on a roadway modernisation project.

The Karl-Marx-Allee Boulevard modernisation project required the removal of the roadway’s concrete layer to a specified level. According to the site manager, the high points along the road were on average about 10 meters apart, so the milling depth changed continuously. In order to ensure the drainage of rainwater, engineers specified a swinging gutter profile over a length of approximately 800 meters and a width of 5.75 meters. Further, the engineering plans required the slope to vary between 2.5% and 3.0% at intervals of 3-5 meters. On the remaining 9.25-meter width of the roadway, the profile had to have a transverse gradient of 2.5% from the centre to the edge of the roadway. This geometry resulted in a constantly changing milling depth between 0 and 12 centimetres.

The project team used a compact milling machine with a milling width of one meter equipped with the Trimble PCS900 3D Milling System. The 3D automatic control system is designed to mill a surface with accuracy to 3 millimetres. With the 3D milling machine, crews were able to produce the profile exactly as planned. The deviations from the terrain model were at most three millimetres from the target value. The milling specialists were also able to undercut the required accuracy of ± 5 millimetres with ease. This created the best conditions for the asphalt pavement, which could then be paved quickly with a constant thickness without the need for time-consuming leveling or compensation layers.

Selecting the right technology enabled solution – 2D, 3D or something in between – is highly dependent on several variables, including project specifications, paver type and crew skills. If you have a specification that is relatively loose and subgrade that is already prepped to an acceptable profile, then 2D paving technology is a perfect application. Also, if your goal is purely smoothness, you might be better off with a 2D system and an averaging beam.

However, if your goal is to improve longitudinal waves over a longer reach than an averaging beam can handle – for example on a project with a lot of vertical curves – then 3D could provide worthwhile benefits. Another value-add to 3D systems is that the technology moves easily from one piece of equipment to another.

At the end of the day, choosing between 2D and 3D, or even something in the middle, shouldn’t be job dependent. Instead, consider the desired outcome and then determine which option best helps achieve that goal. Also, bear in mind that a short-term investment now will provide a lot of job flexibility in the future so that paving contractors can be prepared for any jobsite scenario or specification.

Devin Laubhan is paving product manager at Trimble