Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) legislation is coming in this year, ending months of uncertainty for developers. Here, Martin Lambley, senior product manager for urban climate resilience at Wavin, explains how smart solutions can ensure developments adhere to these new regulations.

A newly published timeline for BNG implementation comes as the first step in getting the legislation on the statute books, meaning developers will be required to deliver a 10% biodiversity net gain on new housing developments this February (for smaller sites, this will be from April 2024).

A ticking clock

Now, more relevant information is trickling down from legislators, including a draft Biodiversity Net Gain Plan and Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) that will give developers greater understanding of what they have to submit to local authorities. But this remains a draft for now, and housebuilders currently need to dig through a number of government department websites to find the plan, and more importantly, the biodiversity metric that gives meaning to ‘10%’ as the magic number for BNG.

This regulatory infrastructure was set to move from draft to law (and hopefully be consolidated in one location) in November 2023, but at the time of writing, we’re still waiting for this rubber stamp. It all makes for a very tight timeline for developers who will need to comply with the regulations in 2024 and are left with an ever-shrinking window to prepare.

What housebuilders can do, however, is become fluent in methods of boosting biodiversity within new developments, so when the time comes, they can act quickly and decisively to ensure the new rules don’t get in the way of progress.

Start at home

There are different routes to achieving the required levels of biodiversity, including on-site, off-site, and credit-based increases, but they aren’t all created equal in the eyes of the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) or certifying local authorities. DEFRA publishes a hierarchy of mitigation that requires avoidance, minimisation, and restoration of impacts before compensation of residual harm through creation or restoration of off-site habitats. Put simply, this means whatever route a developer takes through BNG must start with reducing and reversing the impacts of the project at hand. There are plenty of options available, whatever the project, but housebuilders should ultimately be guided by a wider holistic approach of welcoming nature and biodiversity into new developments as the norm, and embracing the environmental effects and value added to projects.

Building smart

Trees are an important starting point, particularly as they provide more benefits than just increased biodiversity. They can be habitats for a range of species, but also sequester carbon, improve air quality, and make neighbourhoods more desirable – recent research by Wavin revealed that 82% of home buyers consider green spaces important to the buying decision. However, a few saplings here and there won’t cut it; under the new rules, developers must prioritise existing trees and ensure that both new and existing trees included in biodiversity net gain plans are maintained and protected for 30 years.

Building around existing trees and incorporating new ones is often easier said than done, as roots can cause damage to pipework and underground infrastructure. But there are innovative solutions available designed to allow trees to live in harmony alongside developments. They may give them space and water to grow without impacting nearby pipes, or harmlessly repel roots from pipes so they don’t cause leaks or damages.

Supporting sustainable drainage

Blue green roofs are another biodiversity – they turn dead space on flat roofs into intelligent water reservoirs that double up as hubs of biodiversity and habitats for plants, insects, and birds. While innovations like blue–green roofs may look much more green than blue, water is as important to biodiversity as flora and fauna, and how developments handle and leverage water will be crucial to how successful they are in efforts to boost biodiversity.

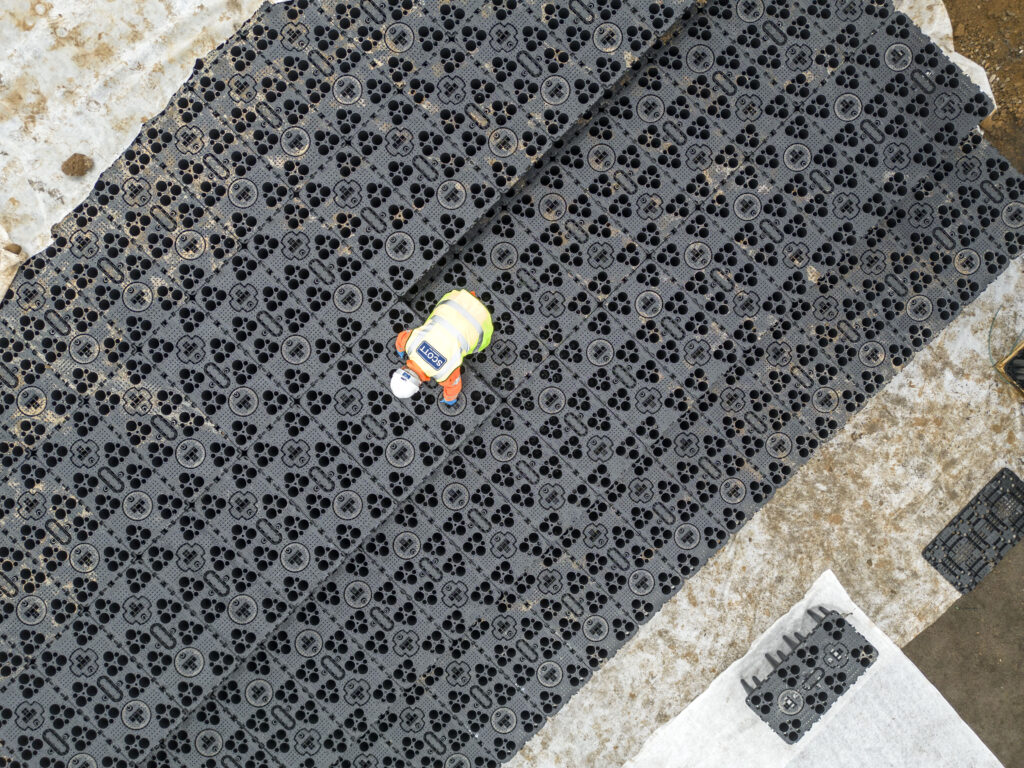

This is where sustainable drainage systems, also known as SuDS, offer the opportunity to add flood resilience and work towards BNG certification – watercourses are a key unit of measurement in the biodiversity metric.

At their best, SuDS combine natural and human-made drainage systems that work to store and redistribute stormwater so that it doesn’t overwhelm public drainage infrastructure. Many natural SuDS such as rain gardens, ponds, infiltration basins and swales all come with benefits for biodiversity or even double as habitats themselves.

How ever they meet BNG requirements, developers will soon have to incorporate SuDS into their projects to comply with parallel upcoming legislation, known as Schedule 3 of the Flood at Water Management Act, which will make SuDS mandatory in new developments. Far from being a legislative headache, this is an opportunity for housebuilders to use the biodiversity-boosting quality of getting natural SuDS right to cover off BNG and Schedule 3 simultaneously.

Adding value

The UK is facing a crisis of biodiversity, and the built environment has more than a supporting role in reversing the trend. But it’s a role that the industry should be proud and not afraid to recognise the value of. Green (and blue) spaces are what many people love about the UK, and the opportunity to live alongside the natural environment will undoubtedly add value and desirability to projects, so let’s do it right and shout about it.

Wavin’s latest whitepaper is The Developer’s Guide: New Biodiversity Net Gain Legislation. It explores why the UK needs a new approach to biodiversity, the fundamental principles and legal requirements relating to BNG and how the rules can boost a development’s bottom line.