Construction Plant News gets the inside story on Stage V from the experts on engine manufacture at Perkins.

In recent times Diesel has been demonised in the popular press as the enemy of air quality, but it is a position which ignores the huge advances that have been achieved in emissions reduction.

Driven by European legislation the technology has been on a remarkable pollution busting journey, with the next stop set for the arrival of Stage V in 2019. The decision on how we power the off highway industry is crucial to the fundamentals of our society; construction, agriculture and heat and light are all industries which owe their existence at least in part to the earthmoving and materials handling equipment that keep them on the move, and across a whole swathe of applications Diesel will for the foreseeable future remain the only game in town.

Perkins has been continually manufacturing diesel engines in Peterborough since the eponymous Frank opened his first factory in 1932, but its founder could hardly have anticipated the advances that have been made since.

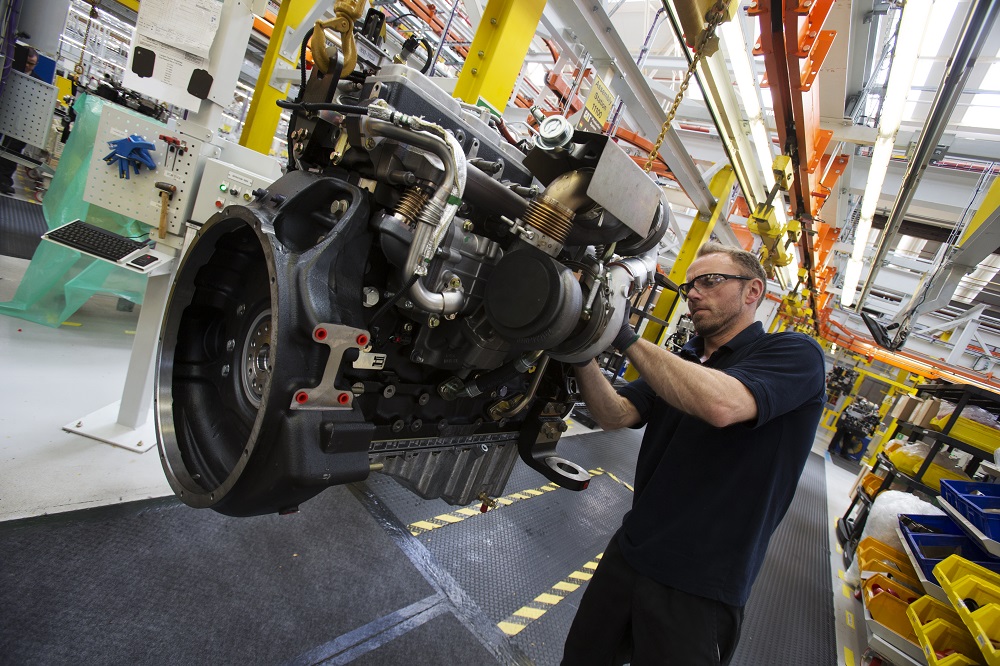

All of the various stages have been designed to reduce both particulate matter and NOx but it’s not just about emissions compliance. It is the first duty of engine manufacturers to produce engines for its customers that are productive, efficient and reliable, which also happen to be emissions compliant, and Perkins is well placed to do just that.

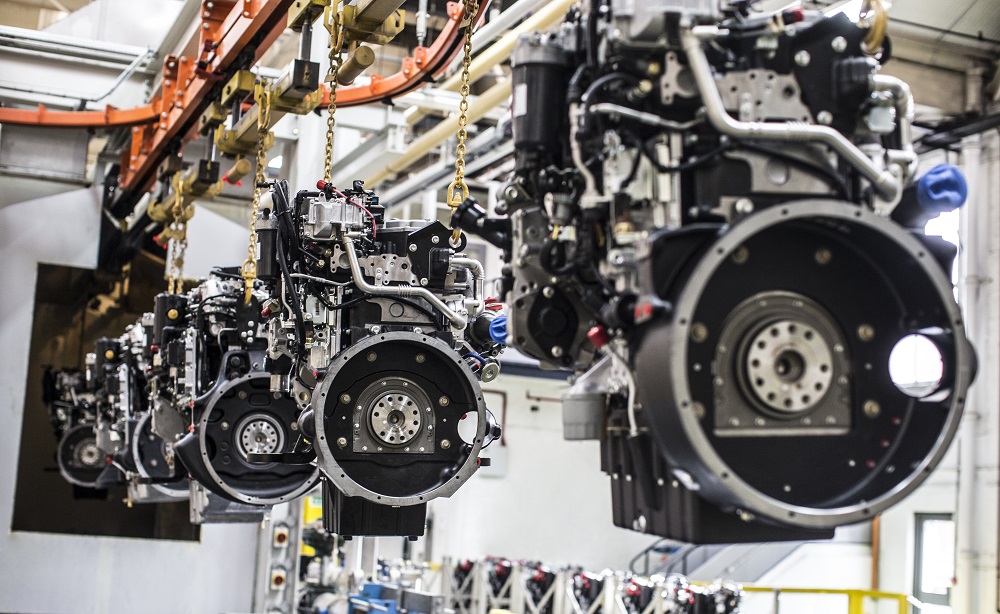

Perkins is a global brand, with over four and half thousand employees, covering 180 countries. Manufacturing facilities can be found as far afield as North America, Brazil, India and China, with parts support in Singapore, the UK and US. The company supplies engines from 6 – 600kW, and spends vast sums of money in research and development, whilst the testing facilities at its Peterborough base bear comparison with anything else in the world.

It is this research and development which is making the gains but just how far have we come? Taking the example of a 75kW/100hp engine, some 20 years ago an unregulated unit would produce 1.6 g/kW.hr of particulate matter. In 2020, with Stage V in place, that will stand at 0.015g/kW.hr, a figure which is a full 120 times smaller.

Grams per kilowatt hour may well not be the most readily understandable measurement so, to put that into perspective, the unregulated 75kW/100hp engine of two decades vintage would effectively emit 6kg of carbon in roughly two months.

Compare that to the Stage V unit of today and it would take more than 20 years to produce the same 6kg level of emissions. Moreover, modern engines in the European market are now required to control particles down to just 23 nanometres.

The technical differences between Stage IV and Stage V are not huge, and certainly do not bear comparison with the previous leap from the III to IV Stages, but perhaps the most significant shift is that all powers will now have some level of emissions control attached. Reductions in NOx remain broadly similar but it is the particulate matter, where Stage V also sees major changes, with the aforementioned 0.015g/kW.hr target.

There are, of course, a number of ways that OEMs and engine makers can achieve these new levels, but regardless of the solution adopted, with regulation levels becoming more stringent at 19kW, 56kW and 560kW, the technology required becomes progressively more sophisticated with increases in power. In the 19 – 56kW range, for instance, Perkins introduces DOC (Diesel Oxidation Catalyst), and DPF (Diesel Particulate Filter) systems.

At the 56 – 560kW level DOC and DPF is joined by NOx-reducing SCR (Selective Catalytic Reduction) with a DEF (Diesel Emissions Fluid), which is, of course, AdBlue. The DOC and DPF system can produce up to 98 per cent filtration efficiency, and the very low particulate mass emissions required of the new regime.

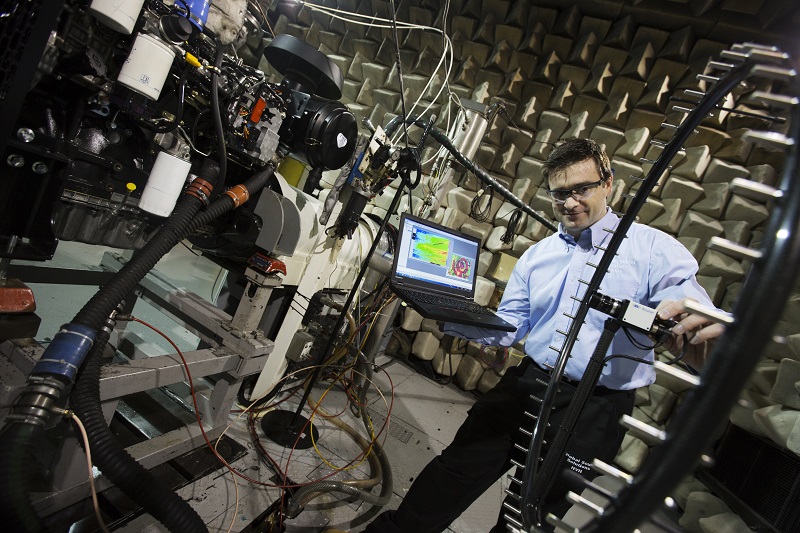

Emissions compliance is a requirement of engine manufacture but what customers are looking for is productivity and reliability across a broad spectrum of applications, and it is combining these demands that represents the real challenge, and necessitates a significant level of field trials. Similarly, new products are subjected to some very aggressive testing in its Peterborough testing centre before they go into production.

Inside the company’s factory, the ‘Track 0’ assembly station is the home of its prototype engines, and is an exact replica of the processes on main assembly lines, enabling Perking to learn how engines can be delivered in mass production at a very early stage. In order to validate a design in the real world as quickly as possible, 3D printed parts can be produced as quickly as overnight.

Peterborough is home to Perkins European Research & Development Centre, and here again entire engines can be 3D printed in order to prepare the testing equipment and to ensure the engine will fit into a given machine, saving considerable time from drawings to test. Emissions legislation is now so stringent that even successfully testing to those standards represents a challenge.

The equipment that weighs filter paper used in particulate matter tests, for instance, will calculate to within 0.1 of a microgram. That means that if you put a full stop on a piece of that filter paper it could accurately calculate the weight of the ink. Test cells will subject engines to an ordeal of hill ascents and descents, and rapid start-ups and cool downs, amongst other scenarios and engines must withstand all these considerable stresses before they can be validated.

All of these processes come together to produce an engine which is remarkably clean, low in fuel consumption – and consequently in CO2 – with the promise of a reliable performance across multiple applications. The next stages in the emissions story might yet be unwritten but what is certain is that reports of the demise of the diesel engine are somewhat premature.

For further information on Perkins click here.