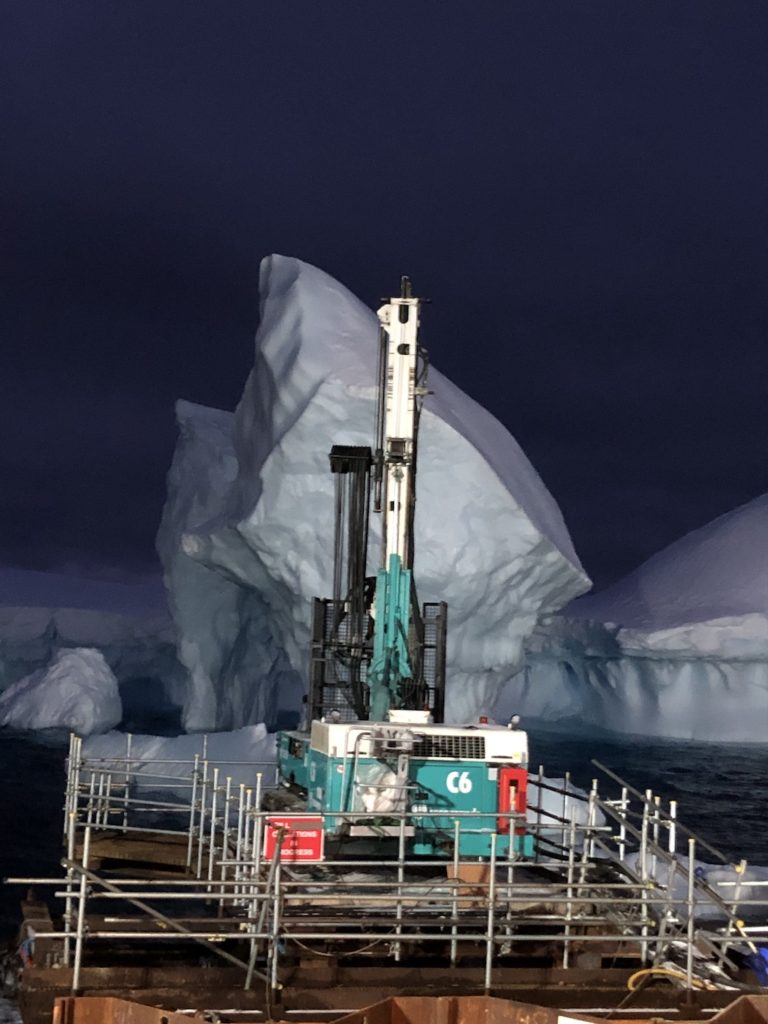

Construction Plant News Editor, Lee Jones reports on the BAM machines that are building vital infrastructure for the British Antarctic Survey in the frozen wilderness of the far south

The seven-year, £300million Antarctic Infrastructure Modernisation Programme (AIMP) will be putting the structures in place to enable the British Antarctica Survey to continue its pioneering scientific work in one of the world’s most unforgiving environments. Beginning in 2018 Phase One has seen the erection of a new utilities facility on Bird Island, continuing with the construction of Rothera Wharf, together with a similar build on King Edward Point, South Georgia.

With the mercury plummeting precipitously during the Antarctic winter, building work can only be undertaken from November to May. BAM Plant Manager, Jasper Blom has been on the ground for every active season since the mobilisation and commissioning of the first pieces of equipment on Bird Island, and has become well acquainted with the demands of managing plant in such an extreme environment.

The AIMP scheme demanded a veritable armada of machinery to be shipped south, as Jasper explains. “Our fleet included a 300-tonne crawler crane, and 75 tonne mobile rough terrain model. In terms of earth moving, in order to facilitate the dismantling of the existing wharf, two CAT 390 excavators were specially fitted with a purpose-built 29metre long reach boom configuration, which were complemented with additional counterweights and extended track frame, whilst four Cat 730 ADTs were utilised, along with a 50 tonne Doosan, and 36 and 8 tonne Caterpillar diggers. In materials handling the construction team needed telehandlers, tractors and trailers at their disposal, whilst the project’s quarrying operation would bring a Sandvik crusher, Finlay screener and Atlas Copco Drill Rig into service.”

It is a testament to the durability of the engineering of the chosen equipment that much of it is left outside during the brutal winter months, when temperatures can regularly descend to -30º and below, before it is resurrected from its icy tomb and made ready for the coming season. Jasper describes the logistics of the operation: “We built a substantial workshop facility on site, and as much of the equipment as possible is housed there, specifically the snow removing machines that will be initially required on our return. Storing a 300-tonne crawler crane inside is not really feasible, however, so these remain at the mercy of the elements.”

The British Antarctic Survey are themselves well-versed in managing machinery in this snow-covered wilderness and they were able to advise the BAM team on the best locations for parking the equipment. Specific winterisation procedures have to be put in place for each piece of plant, which includes removing the engine bay cover plates, for example, so that the snow can be more easily removed from beneath a machine.

“Given the cold, before it is deployed, all of the equipment has to be fitted with 110V electrical systems to pre-heat the engine and oils, whilst dry cell batteries or battery heaters are also utilised for the same purpose. When these are activated they bring the equipment up to a minimum temperature, and remove much of the ice and snow that’s built up during the coldest months. Left in a deep freeze, the viscosity of the oils can change and these need to be brough back to a workable condition. Even with these tools at our disposal, however, there’s still a lot of digging out by hand. It can take around three days to render a crawler crane operational once again, and it’s a process in which we proceed with extreme caution. Any moving components need to be completely free of frozen material or they could blow completely on ignition. The cranes were crucial to the build programme, and a fatal breakdown would be disastrous for our schedule.”

A major infrastructure project is always a daily exercise in problem solving but add one of the world’s harshest environments into the equation and considerable resourcefulness is required. “With a finite store of parts on the Antarctic site, a careful appraisal of which components are most likely to fail is required” continues Jasper, “with high risk items stocked as priority. The remoteness of the location, and its inaccessibility for much of the year, also needs due consideration. If an engine fails it can’t just be flown in quickly, so we have to be careful with our machines, and have sufficient synergy within the fleet to cover for such an issue. In addition, it’s essential to keep ample spares of critical components in our stores.”

All equipment will require pre-start inspections before it’s put to work, but in Antarctica pre-heating becomes an imperative, especially at the beginning and end of a build season, when the temperatures can be particularly low. That includes idling the engine for at least 20 minutes, repeatedly rotating the unit through it full 360º, and stretching the boom, all to ensure that the hydraulics fluids and oils are all at an effective working temperature. “We are provided with a low sulphur marine gas/oil and, whilst it does include additives to stop it from forming paraffin wax at low temperatures, when the thermometers readings get well beneath the minus there are issues with wax build up in the filters and injectors, which is something we have to pre-empt.”

“It’s not necessarily the cold that is a limiting factor for our work but visibility and snow conditions,” Jasper reveals. “Blizzards can make some of the building work impossible, and there are also some problems that are pretty unique to the Antarctic. There are penguins and seals everywhere, for example, so you need to first check that any mammal has not made the space between the tracks or wheels their home.”

Projects within Phase One of the Antarctic Infrastructure Modernisation Programme (AIMP) has been completed to both budget and schedule, and the construction of the new Discovery building will continue in the next season. For Jasper, that’s a testament to the professionalism of the BAM Nuttall team: “Unforeseen issues will inevitably arise on site,” he concludes. “It’s thanks to the competent and skilful people we have in place to first pre-empt any issues through planning and preparation, or to be resourceful enough to overcome them.”